Mine Waste Monitoring

Map, Monitor, Mitigate: Using the HySpex Mjolnir VS620 to tackle one of the world’s worst mining-related environmental treats.

Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) is ranked by the United Nations as the world’s second most pressing environmental crisis after global warming (Parbhakar-Fox and Baumgartner, 2023; Tuffnell, 2017).

The main challenge is the containment of AMD once the weathering process of sulphide minerals has started (Lottermoser, 2010). There are numerous instances where waste management facilities have failed, resulting in environmental disasters like river pollution, widespread contamination with metal-laden sludge, and even loss of human life (Cambero, 2024; Kille and Zimba, 2025; Trevisani et al., 2024).

Economically too, these consequences are devastating for surrounding communities and mining companies alike. For example, the Fundão dam collapse in Mariana, Minas Gerais, Brazil, cost Vale and the BHP Group 32 billion USD.

WHY MONITORING IS CRITICAL AND WHERE HYSPEX COMES IN

Treatments for AMD are available, but no reliable one-size-fits-all solution exists (Kefeni et al., 2017). Therefore, effective monitoring, both during and after mine operations, is essential for enabling prevention and early prediction of AMD problems, thereby minimising their environmental impact. Drone-based hyperspectral imaging offers a revolutionary way to detect AMD risks before they become costly disasters. With the HySpex Mjolnir VS620 system (Fig 1.), you can accurately map key mineral indicators of AMD at centimetre-scale resolution, enabling precise, cost-effective, and proactive remediation.

HySpex, in collaboration with the consortium of Multi-scale, Multi-sensor Mapping and dynamic Monitoring for sustainable extraction and safe closure in Mining environments (M4Mining), advances these strategies by developing drone-borne hyperspectral imaging technology and utilising it as a tool for high-resolution mapping and material characterisation during extraction, re-mining, and environmental impact monitoring (Koerting et al., 2024). The EU-funded M4Mining project is testing its technology at various mining sites to showcase hyperspectral imaging capabilities for different relevant sites. One such site is the abandoned, former sulphur mine Memi in the Republic of Cyprus, which we mapped to evaluate the extent of existing AMD.

Memi is one of many sulphide deposits of the Republic of Cyprus. The hydrothermal mineralisation of Memi likely formed in a classic volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposit (Eddy et al., 1998; Robb, 2005; Adamides, 2010). In 1990 operations at the Memi mine ceased. Waste heaps that are left behind have high concentrations of pyrite (FeS2) and insignificant amounts of copper mineralisation that is not economically viable for reworking the waste material.

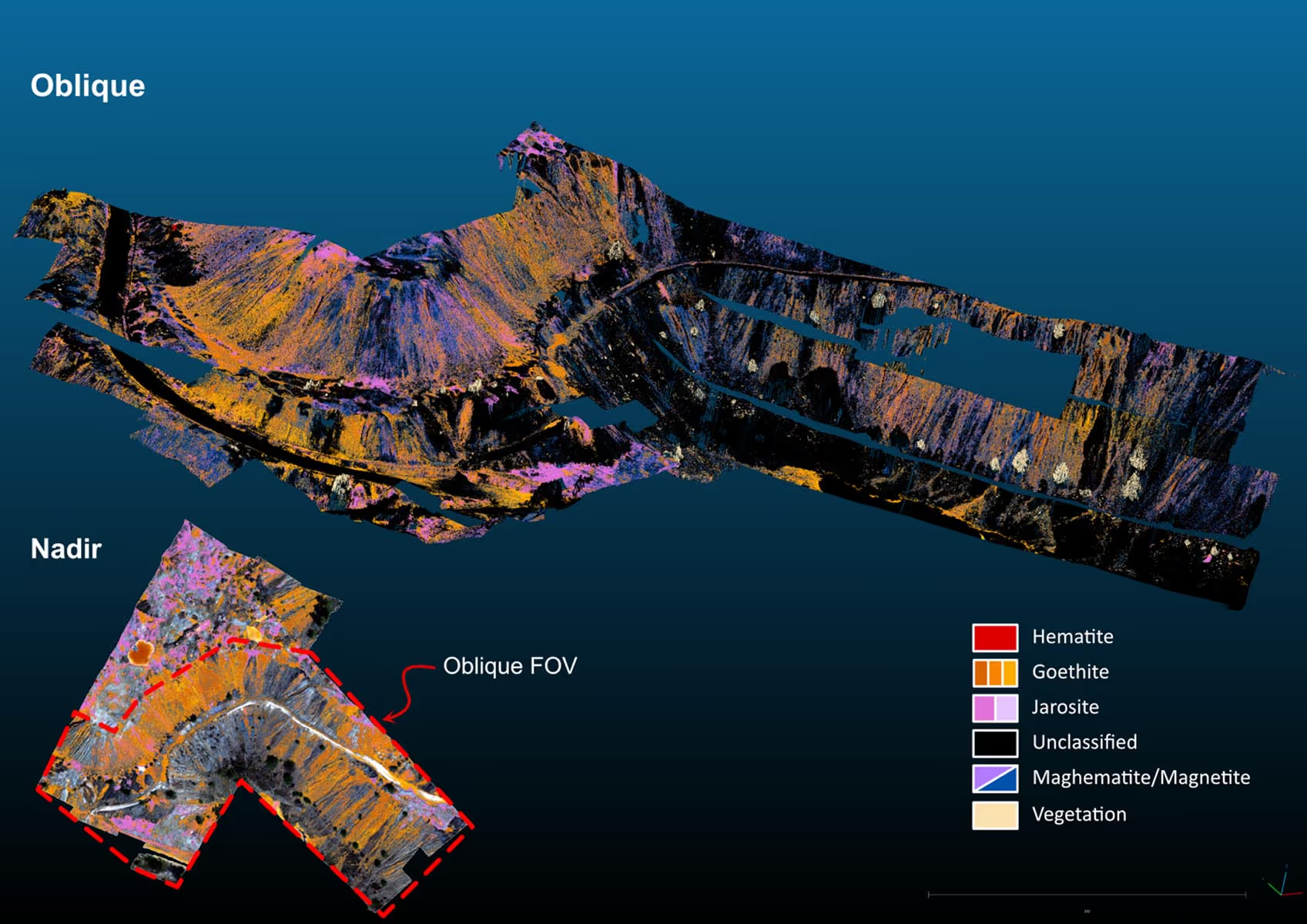

Our industry-leading HySpex Mjolnir VS620 system captures high-resolution data in the visible-near infrared (VNIR, 400-1000 nm) and short-wave infrared (SWIR, 1000 – 2500 nm) spectral ranges. It houses two pushbroom sensors, where the optical axes of the two sensors are co-aligned in the along-track direction to ensure co-registration of captured data in the flight direction. The Mjolnir VS620 is mounted on a stabilising gimbal that enables data acquisition not only in the nadir perspective but also at an oblique angle with up to 40° roll to capture steeper surfaces and slopes.

The drone-mounted HySpex Mjolnir VS620 system was used by M4Mining consortium members in April 2024 to map subtle mineral variations linked to AMD with clarity on the tailings in the North of the Memi mine site. At an altitude of 120 m above ground level, the system yields a spatial resolution of approximately 6 cm and captures a swath about 42 m width (Koerting et al., 2024). From the nadir perspective (birds-eye view, camera pointing straight down), eight flight lines were collected and mosaicked, covering a total area of approximately 11 ha.

For oblique scanning, focus was given to the steep slopes of the waste heaps coinciding with the position of three nadir flight lines. Drone data acquisition took place around solar noon on two consecutive days, under clear skies, ensuring optimal illumination for data collection. Digital surface models (DSMs) were obtained with a mounted LiDAR system, which collects data simultaneously with the Mjolnir VS620, aiding precise geolocation and rectification of the hyperspectral imagery.

The spectral data was processed, georectified, and atmospherically corrected using the PARGE and DROACOR software suite by ReSe Applications, in combination with near-real-time routines for geological mapping developed within M4Mining. For details on HySpex hyperspectral imaging drone data correction and post-processing, see Koerting et al. (2024). However, our HySpex Mjolnir VS620 system is compatible with any other workflow and can integrate smoothly into your monitoring strategy.

FROM PIXELS TO PRIORITIES: MAPPING FOR ACTION

To streamline mineral analysis, we used Breeze Geo by Prediktera AB, which is a software solution fully compatible with our HySpex cameras. Breeze Geo enables efficient classification with the USGS Material Identification and Characterization Algorithm (MICA); a trusted expert system for mineral mapping from the U.S. Geological Survey. USGS MICA automatically identifies minerals in hyperspectral data by matching pixel spectra to reference signatures from a comprehensive spectral library.

The shown mineral maps were created using MICA classification files provided by the USGS within collaborative efforts in CASERM, the Center to Advance the Science from Exploration of Reclamation in Mining. This effort is funded by the National Science Foundation.

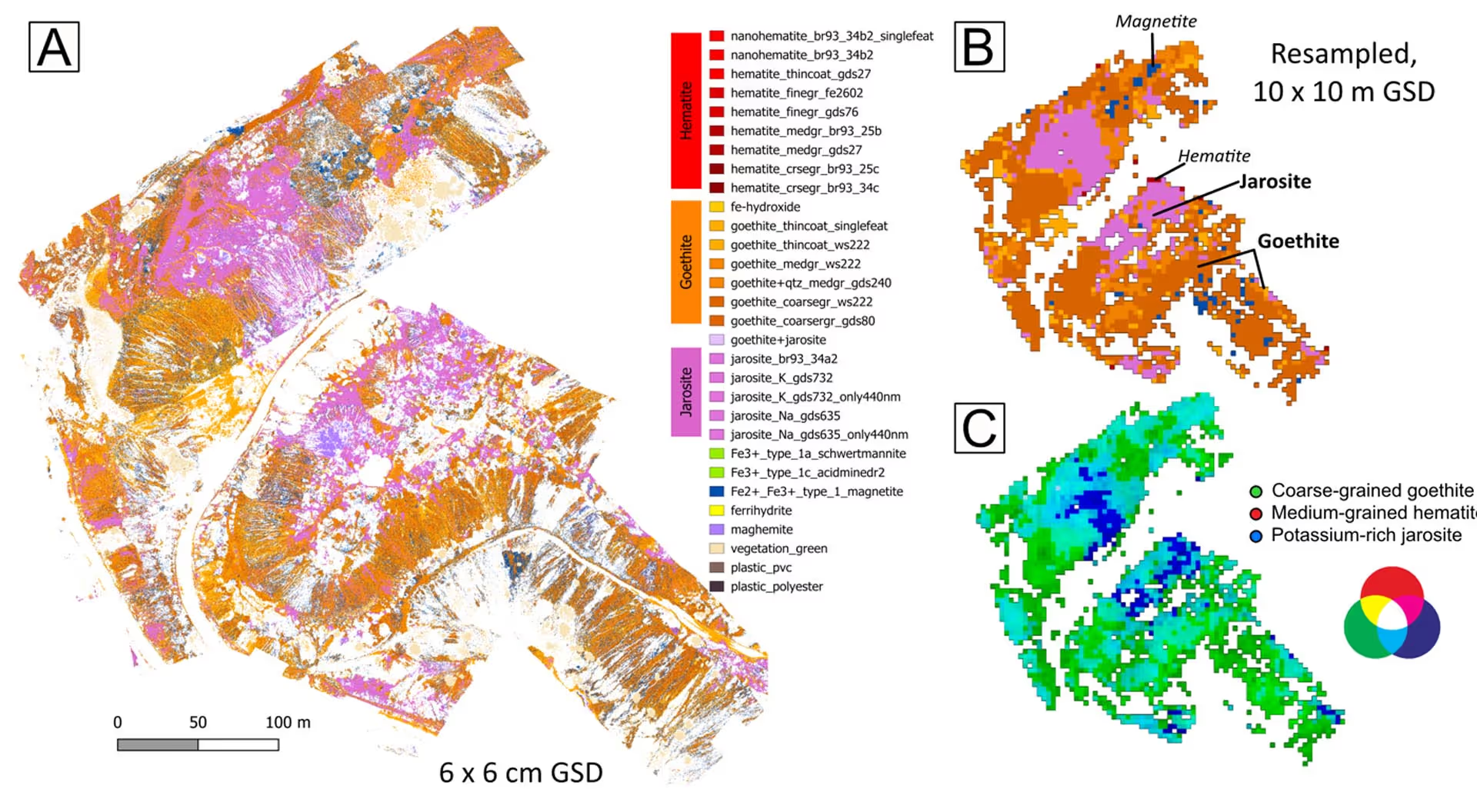

Secondary minerals precipitating during the AMD cycle are pH-sensitive, and, therefore, can serve as proxy for pH mapping (Ong and Cudahy, 2014). These secondary minerals are iron-rich, and many of them are hydroxyl- and or water-bearing, which makes them identifiable through their diagnostic spectral reflectance signatures. Goethite (FeO(OH)) precipitates at pH > 3 under partial neutralising conditions, while jarosite (KFe₃(SO₄)₂(OH)₆) precipitates at pH < 3, thus a strong marker for severe acidity. Hematite (Fe₂O₃), which forms at pH 7-9 (neutral to alkaline), indicates areas unaffected by active AMD. These minerals are mapped using the USGS MICA algorithm creating a classification map of 6 cm pixel size (Fig. 2.A).

To support broader-scale interpretation, we also downsampled the map to a coarser 10 m pixel grid (Fig. 2.B). This facilitates visualization of spatial trends across larger areas, supports regional monitoring and decision-making, and aligns the data with common satellite imagery resolutions for integrated analysis. The pseudo-RGB mineral map (Fig. 2.C) shows the dominant spectral endmembers of the USGS MICA assigned to each pixel. Oblique scans were also analysed using USGS MICA for comparison with the overlapping nadir flights (Fig. 3). The classifications from oblique and nadir scans are largely consistent.

In conclusion, spectral classification confirms jarosite and goethite as dominant surface minerals at the Memi mine tailings, indicating highly acidic conditions (pH ≤ 3) in jarosite-rich areas. Field observations confirm the continued presence of pyrite (key contributor to AMD) in the tailings, suggesting that the AMD process is ongoing and may persist for decades unless mitigated through remediation.

By mapping current surface patterns, remediation efforts can be precisely targeted where they are needed most. Ongoing drone and satellite monitoring will allow for effective tracking of AMD over time, providing valuable insights into environmental changes. This data-driven approach supports smarter, more effective remediation planning and long-term site recovery.

READY TO APPLY THIS TECHNOLOGY TO YOUR SITE?

HySpex offers fully integrated UAV-based hyperspectral imaging systems tailored for mining, remediation, and environmental monitoring. Whether you need a turnkey solution or expert guidance, our team is here to help.

Contact us to learn how hyperspectral data can transform your site assessment and environmental management practices.

Download this application note →

REFERENCES

Adamides, N.G., 2010. Mafic-dominated volcanogenic sulphide deposits in the Troodos ophiolite,

Cyprus Part 2 – A re view of genetic models and guides for e xploration. Appl. Earth Sci. 119,

193–204. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743275811Y.0000000011

Asadzadeh, S., De Souza Filho, C.R., 2016. Iterative Curve Fitting: A Robust Technique to Estimate

the Wavelength Position and Depth of Absorption Features From Spectral Data. IEEE Trans.

Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 5964–5974. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2016.2577621

Cambero, F., 2024. Chile files environmental charges against Anglo American copper mine. Reuters.

Eddy, C.A., Dilek, Y., Hurst, S., Moores, E.M., 1998. S eamount formation and associated caldera

complex and hydrothermal mineralization in ancient o ceanic crust, Troodos ophiolite (Cyprus).

Tectonophysics 292, 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(98)00064-X

Kefeni, K.K., Msagati, T.A.M., Mamba, B.B., 2017. Acid mine drainage: Prevention, treatment options,

and resource recovery: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 151, 475–493.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.082

Kille, R., Zimba, J., 2025. A river ‘ died’ overnight in Zambia after an acidic waste spill at a

Chinese-owned mine. The Independent.

Koerting, F., Asadzadeh, S., Hildebrand, J.C., Savinova, E., Kouzeli, E., Nikolakopoulos, K., Lindblom,

D., Koellner, N., Buckley, S.J., Lehman, M., Schläpfer, D., Micklethwaite, S., 2024. VNIR-SWIR

Imaging Spectroscopy for Mining: Insights for Hyperspectral Drone Applications. Mining 4,

1013–1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining4040057

Lottermoser, B., 2010. Mine Wastes. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12419-8

Ong, C.C.H., Cudahy, T.J., 2014. Mapping contaminated soils: using remotely‐sensed hyperspectral

data to predict PH. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 65, 897–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12160

Parbhakar-Fox, A., Baumgartner, R., 2023. Action Versus Reaction: How Geometallurgy Can Improve

Mine Waste Management Across the Life-Of-Mine. Elements 19, 371–376.

https://doi.org/10.2138/gselements.19.6.371

Robb, L.J., 2005. Introduction to ore-forming processes. Blackwell Pub, Malden, MA.

Trevisani, P., Hoyle, R., Pearson, S., 2024. Miners BHP, Vale Sign $32 Billion Settlement for Deadly

2015 Dam Collapse. Wall Str. J.

Tuffnell, S., 2017. Acid drainage: the global environmental crisis you’ve never heard of. The

Conversation.

Van Ruitenbeek, F.J.A., Bakker, W.H., Van Der Werff, H.M.A., Zegers, T.E., Oosthoek, J.H.P., Omer,

Z.A., Marsh, S.H., Van Der Meer, F.D., 2014. Mapping the wavelength position of deepest

absorption features to explore mineral diversity in hyperspectral images. Planet. Space Sci.

101, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.06.009

We kindly thank the USGS for the continued collaboration in CASERM and for providing

unpublished MICA classification files for testing.